The book of Genesis comes to a close with this sidra, and many of the themes within it are addressed, if not resolved.

The stories of sibling rivalry which began in the very first family with the tension between Cain and Abel and which continue down through the patriarchal enerations finally come to some sort of resolution, with Joseph choosing not to use his power over his brothers to hurt them, as even after all these years they fear he still might. His sons, Manasseh and Ephraim, also do not argue with each other, even when the younger is given special treatment by their grandfather Jacob.

The themes of blessing – in particular the special blessings from father to son, are also addressed: firstly in the blessing by Jacob of Joseph’s two children and the deliberate switching by the bless-er to give the younger one the more advantageous blessing. Somehow when there is no betrayal or rivalry between the bless-ees this is seen as a kind of concluding of the story of dysfunctional sibling relationship, though of course it does leave room for the jealousy to break out once more in the future. But while Joseph protests, his sons do not and sibling rivalry is not a particular theme of the later books of Torah.

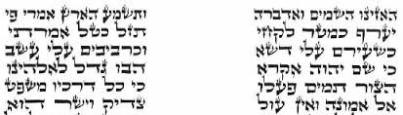

Blessings and the terrible burdens that can accompany them are also made explicit in the way that Jacob speaks to his sons on his deathbed– Reuben is as unstable as water, Shimon and Levi given to violence, Judah has the vigour and nobility of a lion, Zebulun would have a favourable territory with good coastline, Issachar is a large boned ass – physically strong and placid, Dan will be a judge but also a wily cunning foe, Gad would be constantly raided and raiding others, Asher will be happy and rich, Naftali would be both physically graceful and eloquent of speech, Joseph would be fruitful and honourable in the face of difficulties, someone who would surpass his victimhood, Benjamin would be a ravening wolf – warlike and terrifying.

Can we say that these are blessings in any sense that we understand today? They seem to be comments on the characters of his children for them to learn from, or aspirations for them to live up to, rather than calling for the protection and support of God for them.

It also leads us to ask the question: is the expectation of our parents something that can or should shape our lives?

Many of the blessings refer to the names given to the boys at birth – Dan, Asher, Gad, Naftali and Joseph all have names which imply characteristics or aspirations. Some of the blessings refer to actions we already know about – Reuben having betrayed his father with his concubine, Shimon and Levi whose violence to the Shechemites when their prince took Dinah has caused real heartache to Jacob that it seems he cannot let go even as he lay dying. Some of the blessings seem to refer to later events that he cannot have even dreamed of. The descriptions contained in these final words have a power and a hold long after their creator has left the scene.

The deathbed scenes of Jacob and Joseph are narrated dispassionately in Torah. The point is made that both father and son are keen to be buried back in their ancestral home, not in Egypt where they are accorded so much honour. Both remember the promise that has been passed down their family, that God will remember them and will bring about their establishment upon the Land we know as Israel. They are pragmatic about their dying, passing on no material artefacts but certainly transmitting ethical imperatives to their descendants. Connection to the Land and honest evaluation of oneself along with proper thought about how one behaves in life, seem to be the two fundamental lessons they have to give their family.

Reading this final sidra in Genesis, named “Vayechi – And he lived” which primarily details the transmission of values after death, we are prompted to ask “What can we leave to our children that will resonate in their lives long after we ourselves are gone?”

One answer is the expectations we lay down for our children that they may internalise without our even knowing it – a sense of right and wrong, of honourable and ethical behaviour, of common purpose with our both our particular family and with the rest of humanity. We can teach them about God, about our history, about our connectedness to the other. We can teach them that one life is simply that – a life well lived will provide a strong link to both past and future, that there is a longer time scale than our own conscious existence. We can teach them that actions have consequences, that behaviour shapes character as much as character can shape behaviour. We can teach them that there is a great diversity in the world, and that everyone contributes something of value, be they passive or go getting, be they solid citizens or free spirits.

What is important is that we too begin to evaluate honestly our selves and the life we have lived so far, think seriously about what will be read into how we have lived, consider how we will be remembered after we are gone.

The end of a book of Torah is always a powerful reminder that endings are part of the cycle, and this particular sidra, with its emphasis on both life and death remind us to take a moment and consider. A lot of the most painful problems in the stories of the human relationships in this book are finally ironed out as people forgive, let go, learn, change. We are ready to face the next book which will take us into a different world, full of people who remember their history and people who have forgotten everything that came before. Winter is here, we are into the last month of the year and we are becoming aware of how the secular year is turning. Many of us will try to achieve some kind of closure on unfinished problems before embarking on another new year. But before we do that, there is just time to pause and to remember the stories of the early families in Genesis– Vayechi – how we live will impact on a future we can only imagine.