L’italiano segue l’inglese

Kol HaNedarim Sermon 2022 Lev Chadash

The 25 hours of Yom haKippurim are traditionally to be lived from the perspective of as if we are already dead – without food or drink, washing or any social entertainment. While Judaism has no definitive teaching as to what happens after death, there are many rabbinic drashot – sermons or literary constructions – which seek to understand the nature of the soul and its journey from before we arrive in this world to what happens after we leave it

One midrash (Tanchuma : Pekudei 3) has a series of stories about the journey of every soul. It begins by reminding us that every human soul is a world in miniature. It tells us that every soul, from Adam to the end of the world, was formed during the six days of creation, and that all of them were present in the Garden of Eden and at the time of the giving of the Torah.

With every potential new person, God informs the angel in charge of conception, whose name is Lailah and says to her: Know that on this night a person will be formed…. She would take [the potential embryo] into her hand, bring it before God and say: …” I have done all that You have commanded. Here is the drop [of liquid that will become the embryo], what have You decreed concerning it?” And God would decree concerning the embryo – what its end would be, whether male or female, weak or strong, poor or rich, short or tall, ugly or handsome, heavy or thin, humble or haughty. God decreed concerning everything that would happen to it except whether it would be righteous or wicked. That choice alone God left to the individual, as it is said: See, I have set before thee this day life and good, and death and evil (Deut. 30:15).

The midrash continues – while in the mother’s womb the angel would take the soul and show it everything – where it would live and where it would be buried after death; the merit of the righteous souls after death who would live in a beautiful place in the world-to-come, and the distress of the souls assigned to the netherworld because they had not lived righteous lives. The angel would teach the soul the whole of Torah, would warn them about the events that would happen in its sojourn on earth. “And when at last the time arrives for its entrance into the world, the angel comes to them and says: “At a certain hour your time will come to enter the light of the world.” The soul pleads with the angel, saying: “Why do you wish me to go out into the light of the world?” The angel replies: “You know, my child, that you were formed against your will; against your will you will be born; against your will you will die; and against your will you are destined to give an accounting before the King of Kings, the Holy One, blessed be God”. Nevertheless, the soul remained unwilling to leave, and so the angel struck them with the candle that was burning at their head. Thereupon the soul went out into the light of the world, though against their will. Upon going out the infant forgot everything they had witnessed and everything they knew. Why does the child cry out on leaving their mother’s womb? Because the place wherein they had been at rest and at ease was irretrievable and because of the condition of the world into which they must enter. “

I think that we have probably all wondered at some point if, what and where we were before we were born, and more frequently we imagine what might happen after we die. This midrash assumes that we each of us existed always – and will exist always – and that the period that we inhabit the earth is an interlude in which our future will be decided. I am uneasy with the notion that up until birth everything is “bashert” – foretold and “meant to be”. Predestination sits uncomfortably with the notion of free will, and so the rabbinic tradition nuances the idea, declaring that we may be subject to the will of God in our material life, but we are completely free in our spiritual life. This view is most famously found in the teaching of R. Akiva (Avot 3:15): “All is foreseen, yet freedom is granted”; and in the even more powerful dictum of R. Ḥanina, “Everything is in the power of God, except the fear of God” (Ber. 33b; Niddah 16b), and which Midrash Tanchuma (thought to be composed in Babylon, Italy and Israel between 500 and 800 CE) underlines in the passage I quoted earlier.

The Talmud teaches “Everything is in the hands of God except the fear of God” and Midrash Tanchuma tells us that “God decrees concerning everything that would happen to the newly born person except whether they would be righteous or wicked. That choice alone God left to the individual, as it is said: See, I have set before thee this day life and good, and death and evil (Deut. 30:15).

The tradition is trying to address the age-old questions –

Is God interested in us?

Does God have a plan for us?

Does God intervene in history at all?

What is our life about?

Is our life transient or eternal in some way?

Why is life unfair?

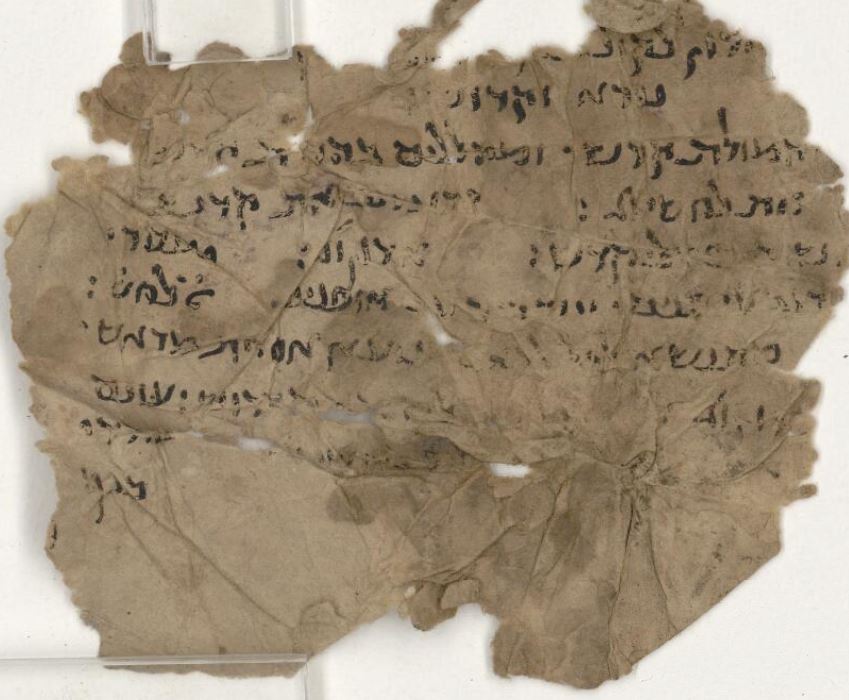

It was a controversy that divided the various sects in ancient Judaism around the first century BCE and the first century CE– the Pharisees – forerunners of Rabbinic Judaism – accepted the idea of the immortality of the soul and they also had some notion – deliberately vague – of reward and punishment after death, while the Sadducees who opposed much of Pharisaic Judaism, did not. The Pharisees developed the role of malachim – what we would call angels – whose activities allowed God to play a role in human affairs, whereas the Sadducees completely rejected both angels and the idea of any divine interference in human affairs, teaching that free will was absolute and unchallengeable. And the Essenes and the Dead Sea Scrolls sect appear to have believed in predestination with no room for any freewill whatsoever. This, I think, puts into context the rabbinic teachings in Talmud and Midrash – they attempt to steer a middle way between two extremes, a technique the ancient rabbis were well practised at but which sadly seems to have attenuated in modern times.

Their middle way – that everything is foreseen yet free will is given, that everything is in God’s hands except for our own relationship with God, that it is up to each of us to decide to behave righteously or not – firmly point to the rabbinic understanding that in all ethical and spiritual matters we are the authors of our own lives. No one else is responsible for these life choices, no one else is responsible for the people we choose to become, or for the decisions we make about how we live our lives.

The word “author”, “authority” and “authenticity” are linked semantically and ideologically at the deepest levels. The author is one who creates, who brings something about, the only one who has the authority to create and to be themselves, their true authentic selves.

The liturgy of this time references the Talmud which tells us that “Three books are opened in heaven on Rosh Ha-Shanah, one for the thoroughly wicked, one for the thoroughly righteous, and one for the intermediate. The thoroughly righteous are forthwith inscribed in the Book of Life, the thoroughly wicked in the Book of Death, while the fate of the intermediate is suspended until the Day of Atonement” (RH 16b). The Book of Life in particular has resonance in the service. Three of the four insertions into the Amidah prayer reference us asking to be written into the Book of Life.

The Sefer HaHayim – usually translated as “The Book of Life” should really be understood as “The Book of Living”. Not an absolute inscription to avoid punishment for this year, but really a request for us to live our true authentic lives in the coming year. To take responsibility, to become the authors of our own story, not pallid replicas or what might matter, or living in the way we think others think we should be living, but to take our authority seriously and to make something special and individual in our lives, allowing ourselves to unfold and to give voice to our deepest and truest selves.

The stories in midrash Tanchuma remind us that each of us is as valuable, as important, as cherished as anyone else. Our souls were all present in the Garden of Eden, our souls were all present at Sinai, our souls each encompass a whole unique world. We dwell in eternity, and we have a few passing years while on this earth to understand and to express ourselves, to let our complexity and our uniqueness blossom, to become our true and unafraid selves. God gives this gift to us and asks us to live, to be the authors of our lives, to fulfil our purpose in creation.

This night of Kol HaNedarim and the hours that will follow it are an invitation to us. Leaf through the pages of our personal Sefer HaHayim and ask ourselves – is this the way we want to be living our lives? Is this the story of our true authentic selves?

We are the authors of the book our lives. And a new page is ready to be written. What will you write?

Kol HaNedarim – Sermone 2022 Lev Chadash

Di rav Sylvia Rothschild

Le venticinque ore di Yom HaKippurim, tradizionalmente, devono essere vissute in una prospettiva che richiami l’idea di essere come già morti, senza cibo o bevande, senza lavarsi e senza qualsiasi intrattenimento sociale. Sebbene l’ebraismo non abbia un insegnamento definitivo su ciò che accade dopo la morte, ci sono molte derashot rabbiniche – sermoni o costruzioni letterarie – che cercano di comprendere la natura dell’anima e il suo viaggio, da prima dell’arrivo in questo mondo a ciò che accade dopo averlo lasciato.

Un midrash (Tanchuma: Pekudei 3) ha una serie di storie sul viaggio di ogni anima. Inizia ricordandoci che ogni anima umana è un mondo in miniatura. Ci dice che ogni anima, da Adamo alla fine del mondo, si è formata durante i sei giorni della creazione, e che tutte erano presenti nel Giardino dell’Eden e al momento del dono della Torà.

Per ogni nuova potenziale persona, Dio informa Laila, l’angelo incaricato del concepimento, dicendo: “sappi che in questa notte si formerà una persona…” [l’angelo] prende [l’embrione potenziale] nella sua mano, lo porta davanti a Dio e dice: … ”Ho fatto tutto ciò che hai comandato. Ecco la goccia [di liquido che diventerà l’embrione], cosa hai decretato a riguardo?” E Dio decreta sull’embrione, quale sarà la sua fine, se maschio o femmina, debole o forte, povero o ricco, basso o alto, brutto o bello, pesante o magro, umile o altezzoso. Dio decreta tutto ciò che gli accadrà, tranne l’essere giusto o malvagio. Quella scelta soltanto è lasciata da Dio all’individuo, come è detto: Vedi, io ho posto davanti a te oggi la vita e il bene, e la morte e il male. (Dt 30,15).

Il midrash continua: mentre sta nel grembo materno l’angelo prende l’anima e le mostra tutto. Dove andrà a vivere e dove sarà sepolta dopo la morte; il merito delle anime rette che dopo la morte vivranno in un posto bellissimo, nel mondo a venire, e l’angoscia delle anime assegnate agli inferi perché non hanno vissuto vite rette. L’angelo insegna all’anima l’intera Torà, avvertendola degli eventi che accadranno durante il suo soggiorno sulla terra. “E quando finalmente giunge l’ora della sua entrata nel mondo, l’angelo si avvicina e dice: ‘A una certa ora verrà la tua ora per entrare nella luce del mondo’. L’anima supplica l’angelo dicendo: ‘Perché vuoi che esca alla luce del mondo?’ L’angelo risponde: ‘Tu sai, figlia mia, che sei stata formata contro la tua volontà; contro la tua volontà nascerai; contro la tua volontà morirai; e contro la tua volontà sei destinato a rendere conto davanti al Re dei Re, il Santo, benedetto sia Dio’. Tuttavia, l’anima non vuole andarsene, e così l’angelo la colpisce con la candela che arde sul suo capo. Allora l’anima esce alla luce del mondo, sebbene contro la sua volontà. Uscendo, il bambino dimentica tutto ciò a cui ha assistito e tutto ciò che sa. Perché il bambino piange quando lascia il grembo materno? Perché il luogo in cui è stato tranquillo e a suo agio è irrecuperabile e per la condizione del mondo in cui deve entrare.”

Penso che, probabilmente, a un certo punto tutti ci siamo chiesti se, cosa e dove fossimo prima di nascere, e ancora più spesso immaginiamo cosa potrebbe succedere dopo la nostra morte. Questo midrash presuppone che ognuno di noi sia sempre esistito, che sempre esisteremo e che il periodo in cui abitiamo la terra sia un intermezzo in cui si deciderà il nostro futuro. Sono a disagio con l’idea che fino alla nascita tutto è “bashert” – “predetto” e “destinato ad essere”. La predestinazione stride con la nozione di libero arbitrio, quindi la tradizione rabbinica sfuma l’idea, dichiarando che possiamo essere soggetti alla volontà di Dio nella nostra vita materiale, ma siamo completamente liberi nella nostra vita spirituale. Questo punto di vista è più notoriamente presente nell’insegnamento di R. Akiva (Avot 3:15): “Tutto è previsto, ma la libertà è concessa”; e nell’ancor più potente detto di R. Ḥanina, “Tutto è in potere di Dio, tranne il timore di Dio” (Ber. 33b; Niddà 16b). Il Midrash Tanchuma (si pensa sia stato composto a Babilonia, in Italia e Israele tra il 500 e l’800 d.C.) lo sottolinea nel passaggio che ho citato in precedenza.

Il Talmud insegna: “Tutto è nelle mani di Dio tranne il timore di Dio” e Midrash Tanchuma ci dice che: “Dio decreta tutto ciò che accadrà alla persona appena nata, tranne se sarà giusto o malvagio. Dio ha lasciato solo quella scelta all’individuo, come è detto: “Vedi, io ho posto davanti a te oggi la vita e il bene, e la morte e il male.” (Dt 30,15).

La tradizione sta cercando di affrontare le domande secolari:

Dio è interessato a noi?

Dio ha un piano per noi?

Dio non interviene affatto nella storia?

Di cosa tratta la nostra vita?

La nostra vita è transitoria o in qualche modo eterna?

Perché la vita è ingiusta?

A tale proposito ci fu una polemica che divise le varie sette dell’ebraismo antico intorno al I secolo a.C. e al I secolo d.C.: i farisei, precursori dell’ebraismo rabbinico, accettarono l’idea dell’immortalità dell’anima e ebbero inoltre qualche nozione, volutamente vaga, di ricompensa e punizione dopo la morte, i sadducei invece, che si opponevano a gran parte del giudaismo farisaico, no. I farisei svilupparono il ruolo dei malachim, quelli che chiameremmo angeli, le cui attività consentirebbero a Dio di svolgere un ruolo negli affari umani, mentre i sadducei rifiutarono completamente sia gli angeli che l’idea di qualsiasi interferenza divina negli affari umani, insegnando che il libero arbitrio è assoluto e incontestabile. E sembra che la setta degli Esseni e dei Rotoli del Mar Morto credesse nella predestinazione senza spazio per alcun libero arbitrio. Questo, penso, contestualizza gli insegnamenti rabbinici nel Talmud e nel Midrash: essi tentano di orientarsi su una via di mezzo tra due estremi, una tecnica in cui gli antichi rabbini erano ben rodati ma che purtroppo sembra essersi attenuata nei tempi moderni.

La loro via di mezzo, in cui tutto è previsto ma esiste il libero arbitrio, in cui tutto è nelle mani di Dio tranne che il nostro rapporto con Dio, in cui spetta a ciascuno di noi decidere di comportarsi rettamente o meno, punta fermamente all’idea rabbinica che in tutte le questioni etiche e spirituali siamo noi gli autori della nostra stessa vita. Nessun altro è responsabile di queste scelte di vita, nessun altro è responsabile delle persone che scegliamo di diventare, o delle decisioni che prendiamo su come viviamo le nostre vite.

Le parole “autore”, “autorità” e “autenticità” sono legate semanticamente e ideologicamente ai livelli più profondi. L’autore è colui che crea, che realizza qualcosa, l’unico che ha l’autorità di creare e di essere se stesso, il proprio vero sé autentico.

La liturgia di questo tempo fa riferimento al Talmud, che ci dice che: “Tre libri sono aperti in cielo a Rosh Ha-Shanà, uno per il completamente malvagio, uno per il completamente giusto e uno per l’intermedio. I completamente giusti sono immediatamente iscritti nel Libro della Vita, i del tutto malvagi nel Libro della Morte, mentre il destino degli intermedi è sospeso fino al Giorno dell’Espiazione” (RH 16b). Il Libro della Vita, in particolare, ha risonanza nella funzione. Tre dei quattro inserimenti nella preghiera dell’Amidà fanno riferimento a noi che chiediamo di essere scritti nel Libro della Vita.

Il Sefer HaHayim, di solito tradotto come “Il libro della vita”, dovrebbe in realtà essere inteso come “Il libro del vivere”. Non un’iscrizione assoluta per evitare la punizione per quest’anno, ma una reale richiesta a noi stessi di vivere la nostra vera vita autentica nell’anno a venire. Assumerci la responsabilità, diventare gli autori della nostra stessa storia, non pallide repliche di cose che potrebbero importare, o vivere nel modo in cui pensiamo che gli altri pensino che dovremmo vivere, ma prendere sul serio la nostra autorità e creare qualcosa di speciale e individuale nella nostra vita, permettendo a noi stessi di realizzarci e di dare voce al nostro io più profondo e vero.

Le storie nel Midrash Tanchuma ci ricordano che ognuno di noi è prezioso, importante e amato come chiunque altro. Le nostre anime erano tutte presenti nel Giardino dell’Eden, le nostre anime erano tutte presenti nel Sinai, ciascuna delle nostre anime racchiude un intero mondo unico. Viviamo nell’eternità e abbiamo pochi anni che passano mentre siamo su questa terra per capire ed esprimerci, per far fiorire la nostra complessità e la nostra unicità, per diventare il nostro sé vero e senza paura. Dio ci fa questo dono e ci chiede di vivere, di essere gli autori della nostra vita, di realizzare il nostro scopo nella creazione.

Questa notte di Kol HaNedarim e le ore che la seguiranno sono un invito per noi. Sfogliamo le pagine del nostro personale Sefer HaHayim e chiediamoci: è questo il modo in cui vogliamo vivere le nostre vite? È questa la storia del nostro vero sé autentico?

Siamo gli autori del libro delle nostre vite. E una nuova pagina è pronta per essere scritta. Cosa scriveremo?

Traduzione dall’inglese di Eva Mangialajo Rantzer