paper written for a rabbinic conference on reforming religion

One of the questions we ask ourselves and repeatedly try to answer, albeit not with great success or satisfaction is: – what is Reform Judaism? Rabbi Morris Joseph in his sermon at WLS asks the very same question at the turn of the 20th Century, saying “It may not be superfluous to point out that Reform does mean something. Not all of us, I am afraid, are very clear as to this point…Reform means a great deal more than the organ and no second day festival…Reform stands for a great, a sacred principle, of which these things are but symbols…it is an affirmation of a desire, an intention, to cling faster than ever to all that is true and beautiful in Judaism. ..Reform has, first and chiefly, to convert those who have ranged themselves under its banner to nobler ideals of living. This is the great truth which nearly all of us miss. Reform is not a movement merely; it is a religion, a life. …it is not merely the expression of a creed, negative or positive, but a pledge binding those who identify themselves with it to the highest ideal of conduct, to a higher ideal even than that which contents the non-Reformer.. “One might say that the emergence of Reform Judaism in the late 18th Century was a not a religious development at all, but a European lay initiative, arising from the effects of the Enlightenment. It began by ‘modern Jews’ challenging prevailing traditional religious beliefs and designing a form of Judaism that would enable Jews to be accepted both as individuals and as a group into European society. [Moses Mendelssohn (1729-86), father of the Jewish enlightenment (Haskalah), more than any other forged a way of holding the two worlds together in a way that Spinoza(1632-77) had not been able or willing to do a century earlier ]

Rabbis only got involved much later in the mid 19th century, and by using academic study (Wissenschaft des Judentums) tried to formulate ideological and theological positions and to support the emerging Reform innovations. It seems to me that that pattern has continued in European Reform Judaism – the continuing communal challenge to traditional ideas, the continuing desire to be part of the mainstream modern world, coupled with the rabbinic task of creating the bridges which allow for modernity to impact on Judaism without causing it to lose its particular flavour and perspective.

As rabbis, ours has become the task of formulating the ideology and of co-creating the overarching principles that contain and maintain our Reform Jewish values. We take for ourselves the shaping and determining of the boundaries that retain our particular identity, while allowing for the diverse expressions of these principles that will emerge in different communities at different times.

There is a prevalent myth behind many of the challenges to the legitimacy of Reform Judaism that somewhere there must be an objectively authenticated Judaism, (orthodoxy).

But any survey of the history of Judaism will instantly reveal that each generation responds to the needs of its time, adapting to their contemporary political, geographical and historical exigencies. While it may take great pains to profess otherwise, classical Rabbinic Judaism is one long process of change, reformation and adaptation – even now. The rabbinic dictum that Revelation took place only once and for all time, in the form of an Oral Law given simultaneously with the Written Torah at Sinai, and which is to be mined from the text only by the initiated who possess a set of carefully hewn hermeneutical principles, was a device that gave Jews, for many generations, the permission to read the text both exegetically and eisogetically, and thus to keep it alive and relevant. It was a brilliant device, but somewhere along the line a distortion has appeared so that the notion of one given Revelation which is unfolded by the knowledgeable and trained elite seems to have become frozen, and with it congealed the ongoing and dynamic process of Jewish response to the world. Scholars began to argue over minutiae rather than focus on the Reality the minutiae were designed to remind them of. The purpose of lively debate became to prove right or wrong, rather than to increase the richness of the understanding. And suddenly authenticity became something everyone sought uniquely for themselves, while denying it to others.

Progressive Judaism emerged as a reaction to this congealing of responsive Judaism. Its innovative and brilliant insight was that of progressive revelation. Instead of there having been one total disclosure at the theophany which we are still unpeeling, it reframed the rabbinic teaching to produce the same effect with a different instrument. Progressive Judaism taught about Progressive Revelation – as each new person reads the text, there is a possibility of new understanding of the divine purpose.

Unlike classical rabbinic Judaism, this new thing was not considered to have been discovered or uncovered, as having an independent existence. Instead we are clear that it is the interaction between reader and text that brings it into being. By bringing our own experience, our own values into our reading of the text, we bring forth a particular reading which did not pre-exist. We emulate our Creator in this continuing act of creation. By language we cause new things to exist – we call forth new worlds and populate them.In the preamble to the Statement of Principles adopted in 1999 by the Pittsburgh Convention of the CCAR, is the comment “Throughout our history we Jews have remained firmly rooted in Jewish tradition, even as we have learned much from our encounters with other cultures.

The great contribution of Reform Judaism is that it has enabled the Jewish people to introduce innovation while preserving tradition, to embrace diversity while asserting commonality, to affirm beliefs without rejecting those who doubt, and to bring faith to sacred texts without sacrificing critical scholarship”We like to use the language of tradition with modernity, continuity with change – we present ourselves as an evolving expression of the Judaism of the ages, so that in the language of Pirkei Avot, Moses may have received (kibel) Torah at Sinai (whatever that means); handed it on (m’sarah) to Joshua, Joshua to the elders, the elders to the prophets, and the prophets passed it on to the men of the great assembly – and we see ourselves in that chain of tradition, receiving something all the way from Sinai, taking charge of it in our own times.

The website for the Reform Movement tells us “It is a religious philosophy rooted in nearly four millennia of Jewish tradition, whilst actively engaged with modern life and thought. This means both an uncompromising assertion of eternal truths and values and an open, positive attitude to new insights and changing circumstances. It is a living evolving faith that Jews of today and tomorrow can live by”. The front page of the annual report for the Reform Movement makes much of the words “Renewing, Revitalising, Rethinking, Representing – Reform”. The prefix re- meaning “again, back” is only added to verb bases The Movement website presents five core principles: “welcoming and inclusive; rooted in Jewish tradition; committed to personal choice; men and women have an equal place; Jewish values inspiring social change and repair of the world” Reform Judaism calls itself ‘Living Judaism’. We see ourselves being in the continuous present – we were not the subject of a Reformation, once and for all, but are always in the process of reforming our theological understanding and its practical expression. And we keep re-forming ourselves. Thus it is important that we have as healthy an interest in the process of how reforming takes place as we have in the content of our Judaism. So we have to ask ourselves – on what basis are we challenging the present and changing the status quo? What are the ways in which we do this? Who is the ‘we’ who is deciding? How is reform happening?

The phrase ‘Living Judaism’ brings us to some interesting places. We recognise Judaism as a living system. And let’s have some definitions here: Living systems are open self-organizing systems (meaning a set of interacting or interdependent entities forming an integrated whole) that have the special characteristics of life, in that they are self sustaining and interact with their environment. They are by nature chaotic. As Meg Wheatley says “If you start looking at the processes by which living systems grow and thrive, one of those is a periodic plunge into the darker forces of chaos. Chaos seems to be a critical part of the process by which living systems constantly re-create themselves in their environment.” ….Living systems, when confronted with change, have the capacity to fall apart so that they can reorganize themselves to be better adapted to their current environment. She goes on to say “We always knew that things fell apart, we didn’t know that organisms have the capacity to reorganize, to self-organize. We didn’t know this until the Noble-Prize-winning work of Ilya Prigogine in the late 1970’s. But you can’t self-organize, you can’t transform, you can’t get to bold new answers unless you are willing to move into that place of confusion and not-knowing which I call chaos.” (Meg Wheatley)

I would like to introduce to you some learning not from the traditional sources, but from the modern world of biology and complexity:

The first is the notion of a self organising system: Self-organization is the process where a structure or pattern appears in a system without a central authority or external element imposing it. This globally coherent pattern appears from the local interaction of the elements that makes up the system, thus the organization is achieved in a way that is parallel (all the elements act at the same time) and distributed (no element is a coordinator). In a self organising system the collective following of a few simple principles can lead to extraordinarily complex, diverse and unpredictable outcomes.

One example is the way that birds flock in the sky. It can be predicated on just three simple rules:

Always Fly in the same direction as the birds around you

Keep up with the others

Follow your local centre of gravity (i.e. if there are more birds to your left, move left. If right, move right)

The second is the idea of punctuated equilibrium: This is a theory that comes from evolutionary biology, which suggests that evolution is not a slowly progressive and continuously ongoing event, but that instead species will experience little evolutionary change for most of their history, existing in a form of stasis. When evolution does occur, it is not smooth, but it is localised in rare, rapid events of change. Instead of a slow, continuous movement, evolution tends to be characterized by long periods of virtual standstill (“equilibrium”), “punctuated” by episodes of very fast development of new forms. Punctuated equilibria is a model for discontinuous tempos of change. According to those who study such things, “Self organised living systems are a conjunction of a stable organisation with chaotic fluctuations.” (Philosophy Transactactions A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2003 Jun 15;361(1807):1125-39. Auffray C, Imbeaud S, Roux-Rouquié M, Hood L.)

Doesn’t it just define Judaism through the ages, and Reform Judaism in our world – A conjunction of a stable organisation with chaotic fluctuations. And these chaotic fluctuations that punctuate our history are the drivers of very fast development and change.I’m sure we can all think of the events – Abram living with his family in Ur Casdim until God says “Lech lecha”. Exodus from Egypt. Sinai. Entering the land; Destruction of first and then second temple, Exile and Return; loss of Northern Kingdom….coming closer to home the development of oral law, of synagogue communities, rabbis taking over from priests in the religious leadership, Karaites; Mishneh Torah, Shulchan Aruch, Expulsion from Spain and Portugal, Moses Mendelssohn and the Haskalah, large scale Aliyah from Russian empire; Salanter and the mussar movement; Hasidim and the lubavitcher dynasty; Israel Jacobson and the Seesen school experiment to name just a few.

The question I have now is – if we truly are a living self organising system, then we are not so much driven by our ideology or our tradition as we are a people whose structure develops without a central authority or external element imposing it. Instead what we become develops from the local interaction of the elements that makes up the system, – that is the people within Judaism. With enough impetus and enough individuals wanting it – or doing it -we become who we are in a way that is parallel (all the elements act at the same time) and distributed (no element is a coordinator).

An example – Pesachim 66a – Hillel could not remember how to carry the knife for the pesach sacrifice on Shabbat. His response was “But,” he added, “things will work out, because even if Jews are not prophets themselves, they are the sons of prophets.” The next day, Shabbat Erev Pesach, these semi-prophetic Jews arrived at the Temple with their animals for the Pesach sacrifice. From the wool of the lamb protruded a knife, and between the horns of the goat a knife was to be found. Upon seeing this Hillel proclaimed: “Now I recall the law I learned from Shemaya and Avtalyon. This is the procedure which they taught me!So how do we hold on to the continuity / tradition we assert is integral to the change /modernity we bring.

Second question – If we do truly function along the lines of punctuated equilibrium, then what are the next things to punctuate our equilibrium? What will bring about the rapid development after our periods of stasis? Should we be looking out for them and encouraging them?

Third question – complex systems emerge from the utilisation of a few very simple rules. Morris Joseph knew what the rules were in Reform Judaism even if, according to his sermon, his congregation on the whole didn’t. Firstly that it was “religious, and that its religious life must be expressed in public worship”. Reform Jews may be “less bound ritually and ceremonially, but are therefore more bound religiously and morally”Secondly that” in order to live, Religion has to adapt itself to the shifting ideas of successive ages”Thirdly, that while progressive Religion is a great idea, progressive goodness is a far greater one. Reform has, first and chiefly, to convert those who have ranged themselves under its banner to nobler ideals of living. Reform is a religion and a life”

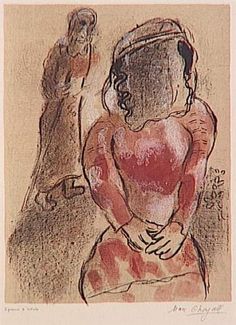

Inserted into the Joseph narratives that take up much of the last half of the book of Genesis, is a chapter about Judah and about his family. It is also a chapter about the actions of a woman who is determined to right a wrong and how she achieves this goal. Situated as it is so discordantly in the Joseph narrative it is easy to turn the page, to ignore the text as we continue to read about Joseph’s troubles and his subsequent elevation. Because it deals with sexual acts, and with apparent impropriety, it is studied much less than it should be. The lens of the narrator is narrow, detail is sparse, but it is a text worth a great deal of attention, for it reminds us that in bible the women were actors in the story and not observers, they were out in the public space, their behaviour often created pivots in the chronicle. The story of Judah and Tamar shouts out “notice me” – the sons of Jacob are yet again challenged by a woman and this time they cannot cheat her or hide from her or marginalise her. Tamar is a risk taker while all the time behaving within the law. She is a model for modern Jewish women, her story reminds us our destiny is in our own hands.

Inserted into the Joseph narratives that take up much of the last half of the book of Genesis, is a chapter about Judah and about his family. It is also a chapter about the actions of a woman who is determined to right a wrong and how she achieves this goal. Situated as it is so discordantly in the Joseph narrative it is easy to turn the page, to ignore the text as we continue to read about Joseph’s troubles and his subsequent elevation. Because it deals with sexual acts, and with apparent impropriety, it is studied much less than it should be. The lens of the narrator is narrow, detail is sparse, but it is a text worth a great deal of attention, for it reminds us that in bible the women were actors in the story and not observers, they were out in the public space, their behaviour often created pivots in the chronicle. The story of Judah and Tamar shouts out “notice me” – the sons of Jacob are yet again challenged by a woman and this time they cannot cheat her or hide from her or marginalise her. Tamar is a risk taker while all the time behaving within the law. She is a model for modern Jewish women, her story reminds us our destiny is in our own hands.